Contents:

I. Introduction

II. Academic Sources

III. Media Analyses

| Contents: I. Introduction II. Academic Sources III. Media Analyses |

"An almost unique phenomenon in Andean music has been the career of Bolivian singer Luzmila Carpio, whose period of exile in Paris resulted in her becoming well known and respected as a musical ambassador for her people. Carpio still lives in France, although she is a regular visitor to her home in the province of Norte Potosi. On albums like Warmi (Woman, 1998) she contributes songs aimed at raising political consciousness and levels of education" (Richards, 35).

With Latin America's history of European colonization, it comes as no surprise that the mainstream musical traditions of the continent are written and performed in Spanish and Portuguese. But many indigenous populations, along with their languages, still exist to this day. Although their cultures have suffered centuries of oppression and erasure, indigenous artists continue to create music in their mother tongues. My Digital Research Project focuses on one such artist, Bolivian folk singer Luzmila Carpio. Carpio writes and performs in Quechua, a language spoken by indigenous populations inhabiting the highlands of Bolivia. Growing up in the village of Qala-Qala high in the Andes Mountains, Carpio learned the songs of the Quechua and Aymara people. Like many indigenous Bolivians living in the cities, Carpio is also fluent in Spanish, and she began her career as the vocalist of a band performing popular music in Spanish.

In the 1970s, Carpio began to look towards her Northern Potosi roots for inspiration, composing original songs in Quechua while accompanying herself on an indigenous stringed instrument, the charango. Her lyrics promote awareness of issues faced by native peoples of the Andes, by women, and by the working class. Carpio relocated to France in the 80s where she continued to write music, eventually working with UNICEF to record the Yuyay Jap’ina tapes to promote native language literacy among indigenous Bolivians.

Carpio’s artistry and activism in her home country of Bolivia and while representing her culture abroad led President Evo Morales to appoint her the Bolivian Ambassador to France in 2006. My research project aims to introduce Luzmila Carpio as a pioneering singer-songwriter in the context of the political and social climate surrounding her career by highlighting themes of indigenous welfare and decolonization found in both Carpio’s music and contemporary Bolivian politics.

Rosaleen Howard-Malverde discusses the pros and cons of Yuyay Jap’ina ("let's grasp awareness"), the UNICEF literacy program for Quechua-speaking women. The region where Luzmila Carpio grew up, Northern Potosi, is among the most economically disadvantaged in Bolivia. Quechua is widely spoken in this rural community, but historially there has been no written tradition. As Howard-Malverde points out: "speakers of languages that function by and large in the oral channel alone, such as Quechua and Aymara, are doubly disadvantaged by the standards of a dominant society that deems ‘civilisation’ a condition only achievable through acquisition of literacy skills and competence in Spanish" (183). The goal of Yuyay Jap'ina, therefore, was to combat poverty and social inequality through mother tongue literacy rather than assimilation through literacy in Spanish.

In terms of education, the women of Northern Potosi have far less opportunity than the men. This became clear during the process of employing teachers, an endeavor to recruit qualified individuals from within the local native population instead of "outsiders to the communities — culturally and linguistically foreigners[...]in relation to their pupils" (185). As a result of so many of the women not being able to meet the minimum education level required, instructors skewed heavily male.

The Yuyay Jap'ina curriculum alternated reading and writing activities with singing, which has a long tradition among the Quechua and Aymara peoples. "The words of songs in the culture of Northern Potosi are never written; they are composed orally, in spontaneous situations of production, by women not men, and never in the home, but out on the hillsides while herding the flocks, later to be sung to the musical accompaniment of the men on their charangos" (188). Luzmila Carpio recorded the musical material used in Yuyay Jap'ina classes.

This article delves into the meaning of decolonization within modern Bolivian politics, specifically the presidency of Evo Morales. Howard begins by giving the background of the different historical implications of decolonization. In the nineteenth century, decolonization meant creole elites gaining their independence from Spain, but it did not necessarily signify the same sense of liberation for indigenous Andean populations. In fact, "from the standpoint of the Bolivian indigenous and peasant movements, decolonization involves overthrowing the exploitative, unjust, and discriminatory order that persisted beyond independence from Spain and into the twentieth century" (177).

Like Carpio, Morales was born to an Aymara family in the rural Bolivian highlands. As such, he has always been persistent in evoking both his working class and indigenous background; since becoming president in 2006, "a jacket tailored from alpaca cloth in natural colors and trimmed with a woven Andean design" has become Morales's customary attire for all state occasions (184). Additionally, Morales is known for being a cocalero activist, leading the movement in Bolivia to end the crimilization of coca cultivation. The U.S. war on drugs has had devastating effect on the livelihoods of indigenous Bolivian farmers for whom the coca plant has been a staple source of income for many generations. Morales's decolonization also incorporates an agenda of ending U.S. imperialism in Bolivia.

Rather than seeking out people with conventional qualifications for political posts, Morales made his ministerial appointments with a focus on decolonizing strategy. In the matter of appointing Luzmila Carpio to French Ambassador, Morales had the following to say: "She was already our French ambassador. She was a legitimate ambassador. I am merely legalizing our compañera Luzmila Carpio’s status as ambassador in France" (190).

In this essay, the author describes at length her experience of attending live musical performances in Bolivia in the 1980s. Leichtman makes many excursions to the Peña (folkloric nightclub) to hear various musicians play. She describes most of the performers as coming from middle and upper class families, "Bolivian urban professionals who dressed in an ethnic fashion" and ""cultivated" attitude toward the presentation of "folk" music" (32). The scare quotes are hers, not mine, and the musicians she describes strike me as being not unlike the hipsters of our generation, in my opinion.

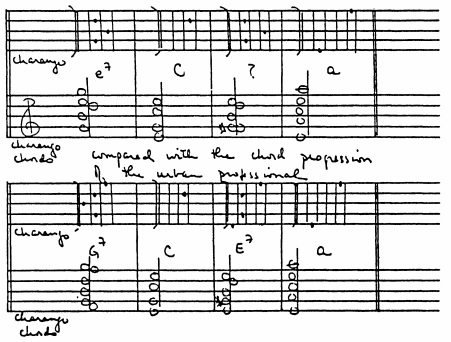

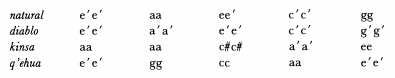

Aside from urban professionals, a different class of performer soon came to Leichtman's attention, and she dubbed them regional professionals. This group, which included Luzmila Carpio, were women from the Potosi lower classes who "sang in high, shrill, nasal tones [...] backed up by charango and sometimes winds" (42) in the indigenous Andean fashion. Leichtman noted that the tuning of the charango as well as the structures of the chords played did not resemble any Western musical conventions. In fact, the tuning of the charango would vary from region to region, even from one individual musician to another.

Leichtman goes on to transcribe the chord progressions she hears and which she describes as dissonant. She also charts various charango tunings.

Fig. 1: Comparisons of charango chord progressions (43) |  Fig. 2: Various ways to tune the charango (49) |

It is important to keep in mind that Leichtman's perspective as a Western trained musician precepts her ability to interpret indigenous music. The five horizontal lines indicating pitches within a stave is in itself a function of Western music notation.

The above recording shows a young Luzmila Carpio in one of her early performances onstage. This piece was written in the mid-1970s when Carpio began to seek inspiration from the folk music of her Quechua and Aymara roots. Dressed in traditional Andean garb, Carpio sings while strumming a five-stringed charango. The traditional form of the charango has ten strings, and the soundbox of the instrument is carved from the shell of an armadillo. The modern charango features a wooden soundbox, because wood has better resonance. It is not clear if the charango is a direct descendent of a particular Spanish stringed instrument, though there is speculation that native musicians were influenced by the sound of the Spanish vihuela.

The Howard-Malverde article on Yuyay Jap'ina explains that the strict assignment of and adherence to gender roles plays a significant part in the daily rituals of Northern Potosi society, and the charango is traditionally an instrument played by men. It is therefore interesting to note that in this performance, Carpio fulfils both the woman's role of providing the vocals and the man's role of accompanying her on the charango. Whether there is a feminist message embedded in this particular performance is uncertain; however, Carpio's later works would go on to address the inequalities faced by indigenous women in unequivocal terms.

The song begins with a series of chord progressions strummed in a repeated pattern. Carpio then begins to sing lightly in a high register. The range of her notes escalates as she transitions effortlessly into her whistle register, vocalizing an entire octave above her first iteration of the melody. The incredibly high range of her vocals is typical of Andean folk singing. I was unable to find any academic resource explaining her vocal technique. Based on my own prior knowledge of Tibetan folk singing, which features similarly vaulting notes with seemingly effortless breath support, I would infer that it has something to do with the lower oxygen levels at high altitudes, a geographic factor that is shared by the Tibetan plateaus and the Bolivian highlands.

The title of the song, "Ama Sua, ama llulla, ama qhella" is based in Incan ideology; translated from Quechua, it means "do not steal, do not lie, do not be lazy". Its message is one of solidarity for the threatened indigenous cultures of Peru, Ecuador, and Bolivia, and a reminder of their shared Incan ancestry. The songs that Carpio would later record for UNICEF's Yuyay Jap'ina project echo these themes: "'no longer to be ashamed of their identity, and to sing with their heads held high, so that everyone should take notice and hear the voice of the people' [in other words] to observe the tenets of the Inca moral code, and to speak the Quechua language" (Howard-Malverde, 189).

This is a video of Luzmila Carpio performing on Miski Takiy, a fairly new Peruvian television program dedicated to promoting indigenous music, which first broadcast in 2010. Carpio's appointment as Bolivian Ambassador to France spanned four years from April 21, 2006 to March 31, 2010; her work abroad served to raise awareness for Quechua and Aymara culture back in the Andean nations of South America. This calls to mind how throughout history, cultural products of Latin America such as the tango first caught on in Europe, which then in turn influenced more domestic acceptance of the music and dance.

In this particular performance, Carpio is no longer performing solo. Instead, she is accompanied by a small ensemble of musicians, and among the ensemble are a guitar and a double bass in addition to the charango. Towards the end of the song, the musicians all join Carpio, clapping and vocalizing the melody. Traditionally, Andean singing involves a single female vocalist and an accompanist on charango and/or pipes. Although this song features a familiar Andean melody, Carpio fuses indigenous elements with European instruments and broader Latin American performance appeal, clicking her heels on the hardwood flooring of the stage and dancing with her musicians.

The music video opens with a shot of a field of flowers backed by the Andes mountains and a clear blue sky. The onstage performance is interspersed with scenes of Luzmila Carpio among many young native women dressed in their traditional garb - knee-length, layered skirts and round, short-brimmed hats. Together, they sing and work in the fields. The final scenes of the music video show men and women dancing in pairs in a large circular formation. The setting has changed from farmlands to city streets. The visual message that comes across to the viewer is that indigenous Andean culture continues to thrive both among the rural populations and those who now live and work in urban environments.

In Luzmila Carpio's long and ongoing career, her musical endeavors have never been stagnant. She began by seeking inspiration from the daily songs of her native people, and has seen her music evolve beyond national borders. The Quechua language, thousands of years old yet still spoken daily by millions, forms the basis of her songwriting and her activism. Her music does not abandon its native, working class roots, and it has a hand in meaningful advancement of indigenous education and representation. Moreover, Carpio's success and the timing of Evo Morales's coming into power is no coincidence; Morales's similar background and leftist politics decidedly amplified Carpio's career, while a conservative, right-wing president from a privileged background would have seen a very different path for Carpio.

Though Carpio has retired from her official position as an ambassador, she continues to perform at home and abroad, collaborating with artists all over the world, singing in Quechua about the ancient, venerated Earth as well as prevalent issues that women, working class, and indigenous populations still face.

Howard-Malverde, Rosaleen. "Grasping awareness: mother-tongue literacy for Quechua speaking women in Northern Potosi, Bolivia." International Journal of Educational Development (1998): pp. 181-196.

Howard, Rosaleen. "Language, Signs, and the Performance of Power: The Discursive Struggle over Decolonization in the Bolivia of Evo Morales." Latin American Perspectives (2010): pp. 176-194.

Leichtman, Ellen. "Musical Interaction: A Bolivian Mestizo Perspective." Latin American Music Review (1989): pp. 29-52.

Luzmila Carpio Remixed, 2015. Web. 8 Apr. 2015.

Minority Rights Group International: Bolivia: Highland Aymara and Quechua, 2005. Web. 8 Apr. 2015.

Richards, Keith. "Popular Music." Pop Culture Latin America!: Media, Arts, and Lifestyle. Ed. Lisa Shaw and Stephanie Dennison. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2005: pp. 9-35.

WOMAD - Luzmila Carpio, 2015. Web. 8 Apr. 2015.

Yuyay Jap'ina Tapes. Bandcamp, 2014. Web. 8 Apr. 2015.

Philomela Gan, 2015 April 30